As more of our daily lives take place online, we have become used to providing companies and platforms with our personal details. Social networks know our birth dates and relationship status, they know who’s birthday party we went to last week and how we feel about the latest elections. Retailers receive our credit card information and remember which products we like best. The benefits of enjoying a seamless online experience tend to outweigh the risks. We have come to trust whoever wants to know more about us, as long as they can offer us an easier and more personalised service.That is, until this trust is broken. Whistleblowers and data leak scandals have become a news staple. In July 2018, the department store chain Macy’s reported that credit card information of thousands of their online customers had been compromised. Are these data leaks going to irreparably damage our trust in large organisations?

Looking at recent changes in personal and financial data legislation, major breaches in the trust we have invested in large companies and institutions stand out as the prime instigators for change. Large-scale data leaks and whistleblowing from within powerful organisations in the last few years have shone a light on just how much privacy we as a society have given up. Public opinion has been causing major shifts in data protection laws, such as the introduction of GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation)by the EU. Society is considering the issues around data privacy and, consequently, data transparency.

Our relationship with trust is in a constant state of flux but which factors might affect our levels of trust in the next ten years?

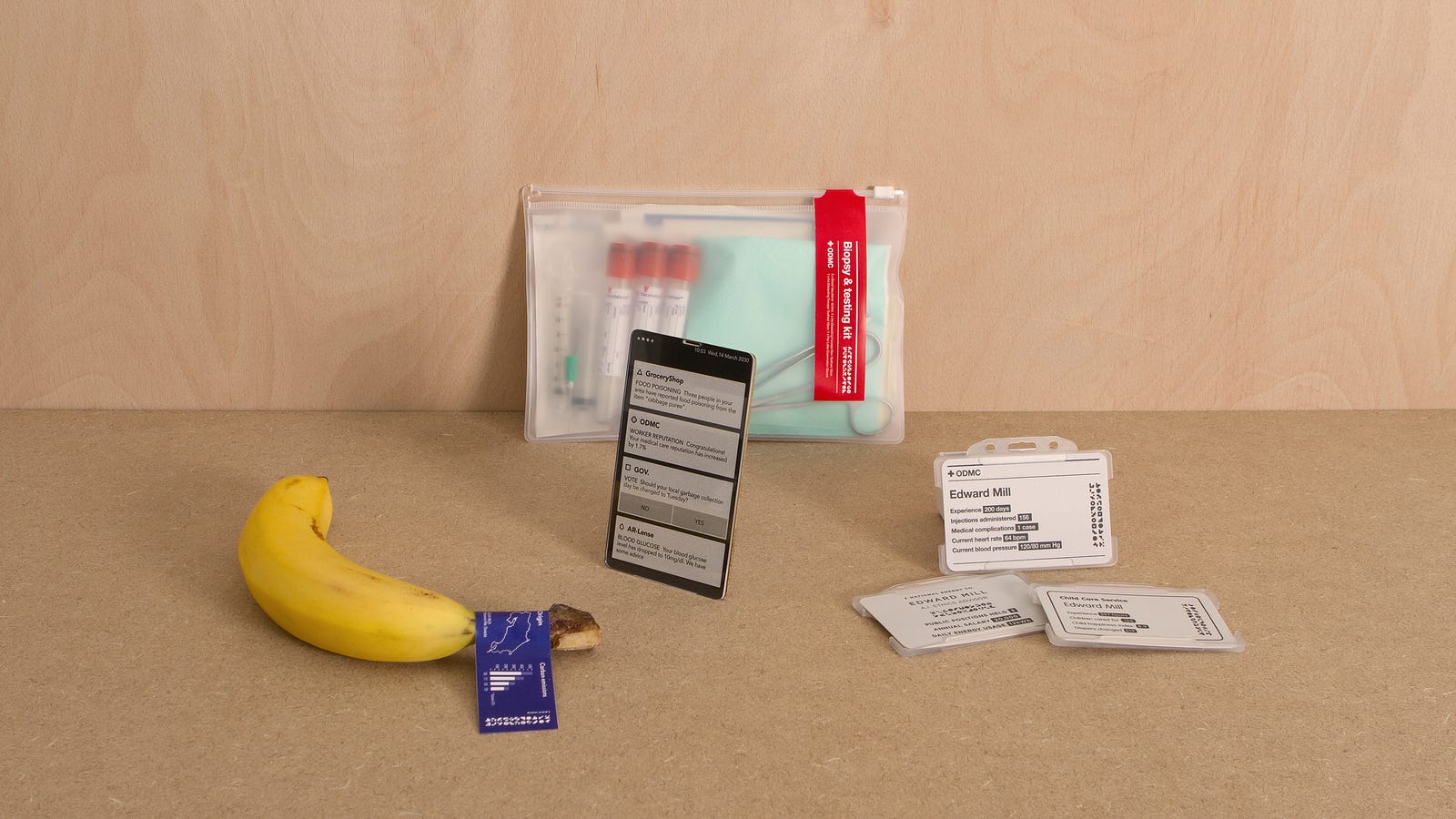

For the Trust/2030 project, the Method team explored what could happen, if a major data breach changed society as we know it. They hereby took into consideration how our relationship with trust has evolved over time, how we process external factors to establish trust and which trends are already apparent in our society today. Three speculative visions of society emerged from the team’s explorations: Decentralised & Transparent, Centralised & Curated, and Distributed & Autonomous. The primary goal was to explore how each society differs from the other and how those differences alter our relationship with trust. Each scenario was brought to life by a ‘future archaeology’, comprised of thought-provoking artefacts that visualise the objects and tools citizens may use in their everyday lives.

Society 1: Decentralised and Transparent

A major data leak exposes a gross Human Rights violation by a public official and causes an uproar in society. Citizens demand accountability from their leaders. This change in public opinion forces the government to publicly disclose their data, creating a highly transparent and data-driven society. Information we used to think of as private is now shared openly by organisations and individuals alike. All areas of our lives are fully transparent: we can access health records online, research what is in our food and where it comes from and find out how much our colleagues earn. Citizens put trust in big institutions because they believe the full transparency movement keeps them accountable and makes products and services more predictable.

The Decentralised & Transparent society focuses on providing citizens with as much information as possible. Everyday objects feature clear information and are designed using sustainable, naturally sourced materials that allow the data to be the priority. Products display as much information as possible and digital devices even let citizens vote on local matters.

Because of the openness of this society, people have faith in the transparent data provided. They make decisions and form opinions about other people and services by evaluating open information. Equally, there is more awareness of data use and data security. Citizens are more interested to know where products come from and what impact they have.

Traces of this society can already be observed, for example, in today’s awareness of personal data protection (mirrored in recent GDPR and PSD2 regulations) and the increased public interest in previously concealed issues about gender, race and sustainability. While the increased accessibility of transparent data makes citizens in this society feel more empowered, there are challenges in how to highlight the most relevant information or how publicly available information can help to define expertise.

A large amount of data require a lot of responsibility from the citizens. Only if they actively engage with the information provided can they benefit from this new society. But what if people decide the inconvenience isn’t worth the trouble? What if information just isn’t enough to reinstill faith into leading public institutions?

Society 2: Centralised & Curated

The second scenario is, once again, put in motion by a series of government data leaks, only this time, the trust citizens had once put into their elected leaders is irrevocably shattered. Big businesses see an opportunity to provide people with the sense of security they crave and large corporations begin to manage all daily needs, from food to entertainment. In exchange for their personal data, consumers get to benefit from fully personalised products. Prices fall and services become more streamlined, making life for the average person more efficient. In this society, brand loyalty and trust is at an all-time high.

All everyday objects mirror a distinct brand identity. Products feature the consumer’s personal details to make their use easy and smooth. Further instructions or ingredient lists are no longer deemed necessary.

The accuracy and convenience of the products provided are unparalleled and people are proud to let their favourite brand manage their daily lives. The data collected from the citizens is used to further customise and improve services. Citizens trust their chosen brand completely.

Large business acquisitions are already common today (in June 2018, mobile phone giant AT&T acquired entertainment corporation Time Warner) and companies providing a multitude of services, such as Amazon, are as much a part of everyday life today as are virtual assistants like Alexa, another Amazon technology. While we can already observe and benefit from the high levels of convenience and efficiency these developments provide, societies with such extreme levels of centralisation need to address how they can find the balance between helping and controlling people and what should happen if the one corporation that controls so many services fails. Is giving up control over all our data really worth it? What if we could trust neither the government nor big businesses?

Society 3: Distributed & Autonomous

In a world where a series of data leaks exposes the shaky foundation on which the current government had been built, faith in all public institutions, including banks, is lost. A major financial crisis follows and forces people to reorganise society completely. Small communities begin to form who provide their own currency and energy, allowing them to exist completely independently. By reverting to physical security systems, data hacks are no longer an issue. Self-reliance trumps trust in this society.

Citizens are sceptical of each other and try to manage most things by themselves. They carefully select people and communities with whom to interact. There is a heightened awareness of data usage and security. As a result, trust is placed in the tangible and physical, rather than the digital. Object that are created by the communities themselves. Citizens pass on and modify these artefacts, which reflects the DIY nature of this society. Because people can no longer rely on outside institutions to oversee their basic human needs, communities put together manuals that teach them everything they need to know about topics ranging from healthcare to generating your own electricity. People revert to physical security systems, like locks and keys, that are less prone to hacking.

This society might seem extreme but there are many developments already occurring today that reflect an increased distrust in government and the control big businesses exert over their users. Peer-2-Peer services are already observable today: P2P money transferring services like Venmo are hugely popular and there are communities already living off-grid with their own sustainable sources of energy, using local micro-grids and large-scale battery storage for power. But without the help of an advisory third party, how can people find credible sources of information? What purpose can organisations serve in this society and how can they rebuild public trust over time?

Consumer Trust

Of course, we can’t really foresee exactly what 2030 is going to look like. However, all of the potential future societies show elements of the way we engage with and use trust today. One thing is for certain, whether users demand more transparency, decide to completely give control to large corporations or turn their backs on traditional institutions, businesses will have to adapt to consumer demands to retain their trust.

Recent policies that give more control to the consumer prove that users are no longer willing to turn a blind eye to data misuse. People are increasingly aware of issues around environmental change, gender and racial biases and demand more transparency and accurate information. This does not only affect government policy-makers but also companies seeking to create and maintain trust in their products and services.