Evolving Trust

Since last year, Cruise Cars has been preparing to drastically change San Francisco’s ride-hailing landscape. The GM-owned car company began testing driverless cars in the area, in a bid to roll out a robo-taxi fleet by 2019. Even though these vehicles are a far cry from the flying cars many had envisioned to exist in the 21st century, this new technology has raised concerns amongst residents. Cars have been involved in incidents ranging from minor bumps to a cyclist being knocked off of their bikes. Research, however, agrees these accidents are not caused by faulty technologies, Cruise cars follow safety regulations to a T, but because the cars have to interact with (inherently flawed) humans. Yet, even the most forward-thinking person is inclined to trust a human driver more than an AI, for one because we might not understand how its algorithms work but also because a robot doesn’t use the same mechanism to make decisions as we do.

The way we assess situations and the people around us is an important indicator of how we come to trust someone. We decide whether to use, and trust, a new product like the driverless car based on previous experiences, cultural values and advice from our peers, and this is not only true for new products and services. In the age of fake news and the decline of the fact-based society, we’ve been able to witness first hand what happens when people lose faith in the previously highly regarded institutions and experts. Once thought of as the most trustworthy source of information, the Edelman Trust Barometer classifies the media as the least trustworthy institution in 2018.

It has become clear that our society is constantly evolving to adapt to a number of external factors. Our changing values and circumstances have the power to modify laws and regulations and cause market fluctuations. As technology develops at a faster pace than ever before, we are forced to adopt these advancements into our lives. It only makes sense that as our society changes, our relationship with trust evolves too. So, how do we decide whom to trust today?

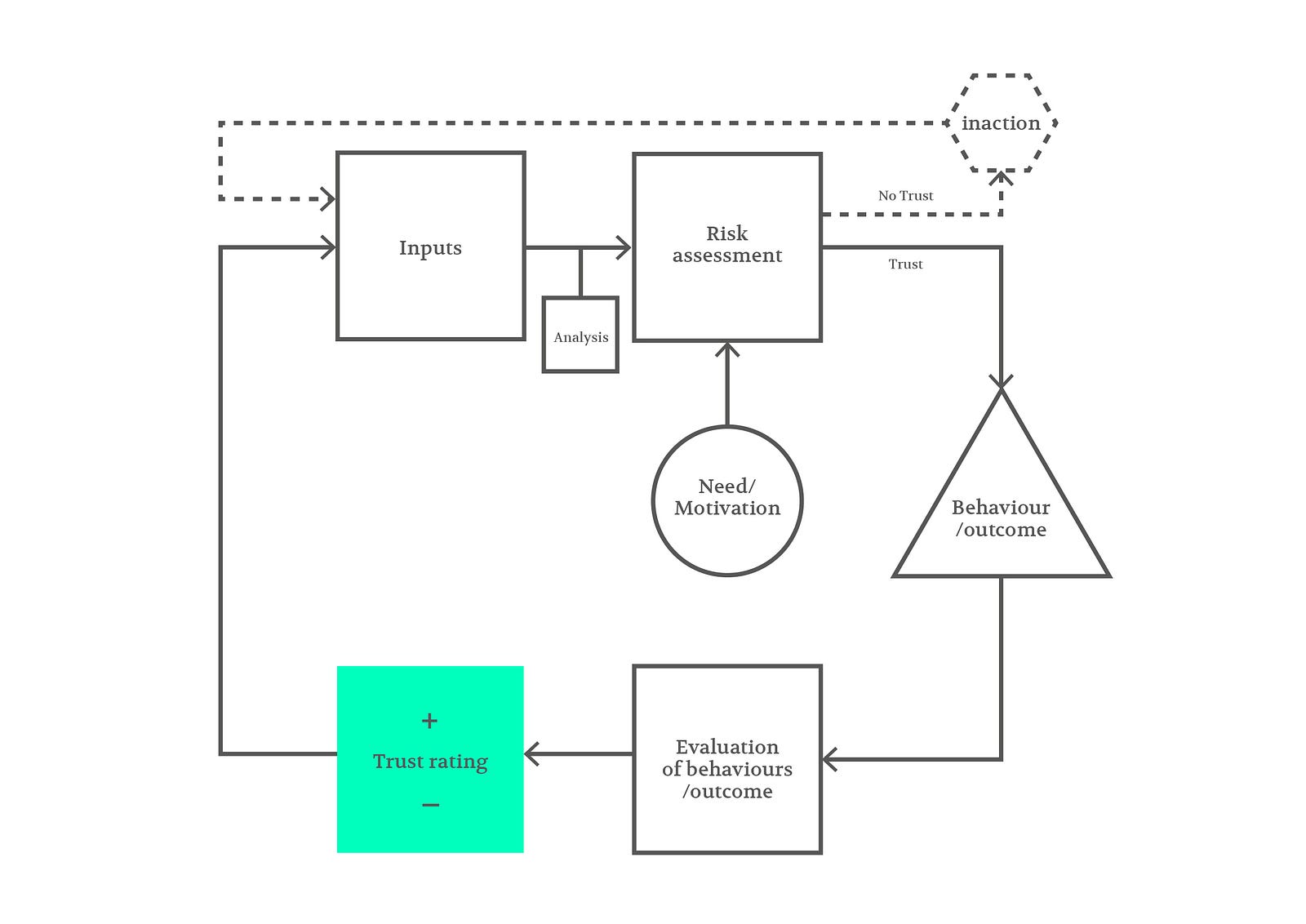

A conceptual model of trust — The Trust Cycle

During our research on trust, we thought about the process of deciding whether to trust a person, institution, product or service. We developed a model of trust, visualised as a feedback loop with various inputs and outputs.

Processing Information: Inputs, Analysis, Risk Assessment and Motivation

How do we know if we can trust someone? The first thing we do is evaluate the inputs we have available to us or, in other words, the information we can gather about someone or something. These can be objective (quantitative), such as company records or statistical data found online, or subjective (qualitative) like our personal experience or familiarity with a certain situation or a person’s reputation. We might trust a local politician because we’ve personally witnessed their involvement in our community but we might decide not to trust a car manufacturer because we read news reports about their emission scandal.

Other inputs are entirely emotional like gut instincts, personal biases or values associated with someone’s upbringing, culture and age. Even small cues, like somebody’s body language, can lead us to choose whether or not to trust a stranger.

Often we are confronted with complex sets of information or large quantities of data that need to be evaluated by a third party. A lawyer can help us with complicated legal documents, companies hire HR professionals to evaluate future employees and a friend can help us decide which broadband provider is the most reliable.

Once we have collected and evaluated all information available, either on our own or with the help of a trusted advisor, and personal values have been considered, we can assess the risks involved in trusting another party. In other words, we have to decide what is at stake. If you buy an unreturnable shirt from eBay, it might not fit. Is it worth trusting the seller and potentially wasting money?

What is at stake is, of course, closely influenced by why we need to interact with a third party in the first place. How much do we rely on this transaction? A patient in a desperate situation has no other choice but to trust their doctor, even if they have never met them before and have no way to verify their expertise because their life is on the line. Other decisions have little or no consequence so that we can choose the safer option rather than trusting the unfamiliar. How much we need a certain outcome can significantly affect our willingness to trust.

Action or Inaction

If we decide to trust another person, the interaction continues and leads to a specific outcome (if we trust a bank will keep our money safe we let it handle our finances) but should we decide not to trust someone or something, we arrive back at square one at which point we might gather more information or re-assess the risks involved. The persistent inability, however, to trust a third party, leads to a loop of inactivity, showing just how important trust is in today’s society. Not being able to find a way to put your faith in other people, institutions or services, makes taking part in society virtually impossible.

Evaluation & Trust Rating

Once we’ve gone through with an interaction, we can evaluate its outcome. If we were able to establish trust, we can add this ‘previous positive experience’ to our input. However, if the outcome is not what we expected then our trust is diminished and we log this interaction as ‘previous negative experience’. This is why we won’t lend someone money who have previously not paid us back or why we won’t buy a product that has let us down in the past.

Continuation

Past experiences offer more information for the next cycle so that the feedback loop is never ‘finished’. Trust is always being assessed and re-assessed. It can never be fully gained or lost, it can only increase or decrease. There can always be another cycle around the loop with new inputs that may change the assessment in the future. Somebody afraid of driverless cars, might change their opinion once they read positive reviews, their friends start using AI operated cars, or they are forced to use one and have a pleasant experience.

Increasing Trust In Products and Services

We wanted to create a model that visualises the process of ‘trusting’ to be able to consider the mechanisms at play when creating and marketing products and services that rely on trust. The model not only helps us understand how trust interactions work, but it also lets us play with and alter some of the factors or inputs at different stages to see how they may affect levels of trust. Does access to more information inputs automatically mean more trust? How can we understand the risk assessment stage? How do people’s needs or motivations change over time?

As expectations of transparency increase, we learn to scrutinise the information available to us. We begin to judge companies and brands by how much each interaction with them increases or decreases our level of trust. As the trust cycle demonstrates, users constantly evaluate new input, re-assess risks and process negative and positive outcomes when dealing with a product or service. Trust is, therefore, a long-term process; it can be easily lost even once it has been earned. Many brands, for example, commit to trust in their brand values but these principles are only effective if they are upheld by all brand representatives, from company employees to the designers tasked with creating a consistently positive user experience.

Unsurprisingly, this has lead to companies leaving conventional branding agencies focused on mere marketing solutions and instead, seek out brand-aware and user-centric product and service design studios to find ways to ensure customers’ trust in their brand is reflected in meaningful user experiences.